Jessica W. Edgar, MD; Christopher N. White, MD

Department of Emergency Medicine, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL

Abstract

A 47-year-old woman with history of lupus anticoagulant positivity, recurrent DVTs and pulmonary embolism with IVC filter presented to the emergency department with a chief complaint of lower abdominal pain and a bilateral lower extremity rash onset hours prior to presentation. Abdominal CTA identified pneumatosis of the small bowel wall concerning for ischemia, descending and sigmoid colon colitis, multifocal narrowing and occlusion of the distal peroneal arteries, and abnormal bilateral renal perfusion concerning for renal infarcts. In conjunction with the patient’s history of antiphospholipid syndrome, now with multi-organ failure because of an overwhelming thrombotic process, there was concern for catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome (CAPS) as the etiology of her presentation. She underwent colonic resection, intermittent hemodialysis, and a course of PLEX therapy for presumed CAPS. She was discharged several weeks later in stable condition with re-initiation of her anticoagulation.

Introduction

Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome is infrequently described in emergency medicine literature. This syndrome, characterized by overwhelming autoimmune mediated microvascular thromboses, has high morbidity and mortality which increases with delayed recognition. We present a case of CAPS in a patient who initially presented in multi-organ failure in the emergency department.

Case

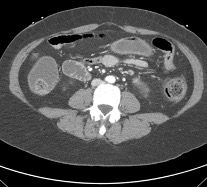

A 47-year-old Caucasian woman with a history of antiphospholipid syndrome, recurrent DVTs and PTE with IVC filter on anticoagulation presented to the emergency department with lower abdominal pain and bilateral lower extremity rash of onset approximately twelve hours prior to presentation. She had diffuse abdominal pain out of proportion to the exam and a bilateral lower extremity purpuric bullous rash. Initial labs showed acute renal failure (Cr 3.9), acute liver injury (ALT 198, AST 652), undetectable fibrinogen level, significantly elevated D-dimer (>20,000), and lactic acidosis (6.3). Abdominal CTA showed small and large bowel, liver and bilateral renal infarctions for which the patient underwent emergent surgical small bowel resection (Image 1). aPL antibodies were initially negative, however were thought to represent dilutional false negatives as they were obtained after massive blood and platelet transfusion. After stabilization of coagulation derangement and eventual extubation, the patient endorsed a long-standing diagnosis of lupus anticoagulant positivity since 2009. Thus, the diagnosis of CAPS was rendered the most likely etiology of her presentation. Following an extensive inpatient course for surgical resection of ischemic bowel as well as systemic corticosteroid and PLEX therapy, the patient was discharged to home on a heparin-to-warfarin bridge. Despite survival from this catastrophic event, she has required several lower extremity digit amputations and is currently being evaluated for bilateral BKAs as sequelae of her initial presentation.

Pneumatosis involving several loops of small bowel (left) in the lower abdomen with extensive

enteric and portal venous gas (right), highly concerning for bowel and liver ischemia/infarct.

Skin manifestations in CAPS may range from a retiform, flat rash pattern to purpuric bullae.5

Discussion

CAPS is a life-threatening immune mediated process hallmarked by diffuse intravascular thrombosis resulting in multi-organ failure. Though infrequently encountered in the emergency department setting, it represents an important consideration in the evaluation of a patient who presents with multi-organ failure. Those organs or systems most frequently involved include: kidney (71%), lungs (64%), skin (50%), gastrointestinal tract (25%), and the arterial system (11%). CAPS closely resembles several other micro-angiopathic processes including DIC, HUS, and TTP; yet it has several unique features that allow for its differentiation. To diagnose CAPS, several criteria must be met: thrombotic involvement of at least three organ systems, manifestation within one week, histologically confirmed evidence of intravascular thrombosis, and the presence of antiphospholipid antibodies noted on two separate occasions, six weeks apart. If all four of the criteria are present, the diagnosis is definite. If less than four but some combination of the criteria is present, the diagnosis is probable.4

Laboratory evidence of CAPS shares some characteristics with other deleterious thrombotic processes.2 For example, thrombocytopenia is seen in CAPS, TTP, HUS and heparin-induced thrombocytopenia; however, the lesser degree of thrombocytopenia seen in CAPS distinguishes it from other microangiopathic processes. A markedly elevated lactate suggestive of tissue ischemia is frequently seen. As is observed in DIC, a significantly decreased plasma fibrinogen level and elevated fibrin degradation products are often observed. DIC can even complicate up to one third of CAPS cases.4

A multidisciplinary approach to treatment is essential to improving outcomes, as CAPS carries a mortality of nearly 50%.1,5 Treatment begins with the emergency physician’s recognition of patients presenting with multi-organ failure and laboratory evidence resembling DIC. Emergent surgical consultation is essential for early operative management of organ ischemia. Consultation with nephrology, rheumatology and hematology is essential as patients may require inpatient dialysis, transfusions, and plasma exchange or glucocorticoid therapy.

References

- Asherson RA. Multiorgan failure and antiphospholipid antibodies: the catastrophic antiphospholipid (Asherson’s) syndrome. Immunobiology. 2005;210(10):727-733.

- Espinosa G, Bucciarelli S, Cervera R, Gómez-Puerta JA, Font J. Laboratory studies on pathophysiology of the catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. Autoimmunity Reviews. 2006;6(2):68-71.

- Firestein GS, Erkan DS, Salmon JS, Lockshin MS. Kelley and Firesteins Textbook of Rheumatology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier; 2017.

- Nayer A, Ortega LM. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome: a clinical review. J Nephropathol. 2014;3(1):9–17.

- Vora SK, Asherson RA, Erkan D. Catastrophic antiphospholipid syndrome. J Intensive Care Med. 2006;21(3):144–159.